Explore the soul of southern Spain on a scenic day trip from Seville. Climb a castle above a shimmering lake, roam a village carved into rock, and ride mountain roads through endless olive groves as you discover Zahara de la Sierra, Setenil de las Bodegas, and Ronda.

Castles, Caves and Contraband, Spain's Most Epic Day Trip

Most Americans arriving in Spain envision Barcelona’s beaches and Madrid’s grand boulevards. But Andalusia, Spain's southern region, is a different world entirely, with its sun‑drenched hills, whitewashed villages clinging to cliffs, turquoise reservoirs, Moorish castles, and incredible bridges.

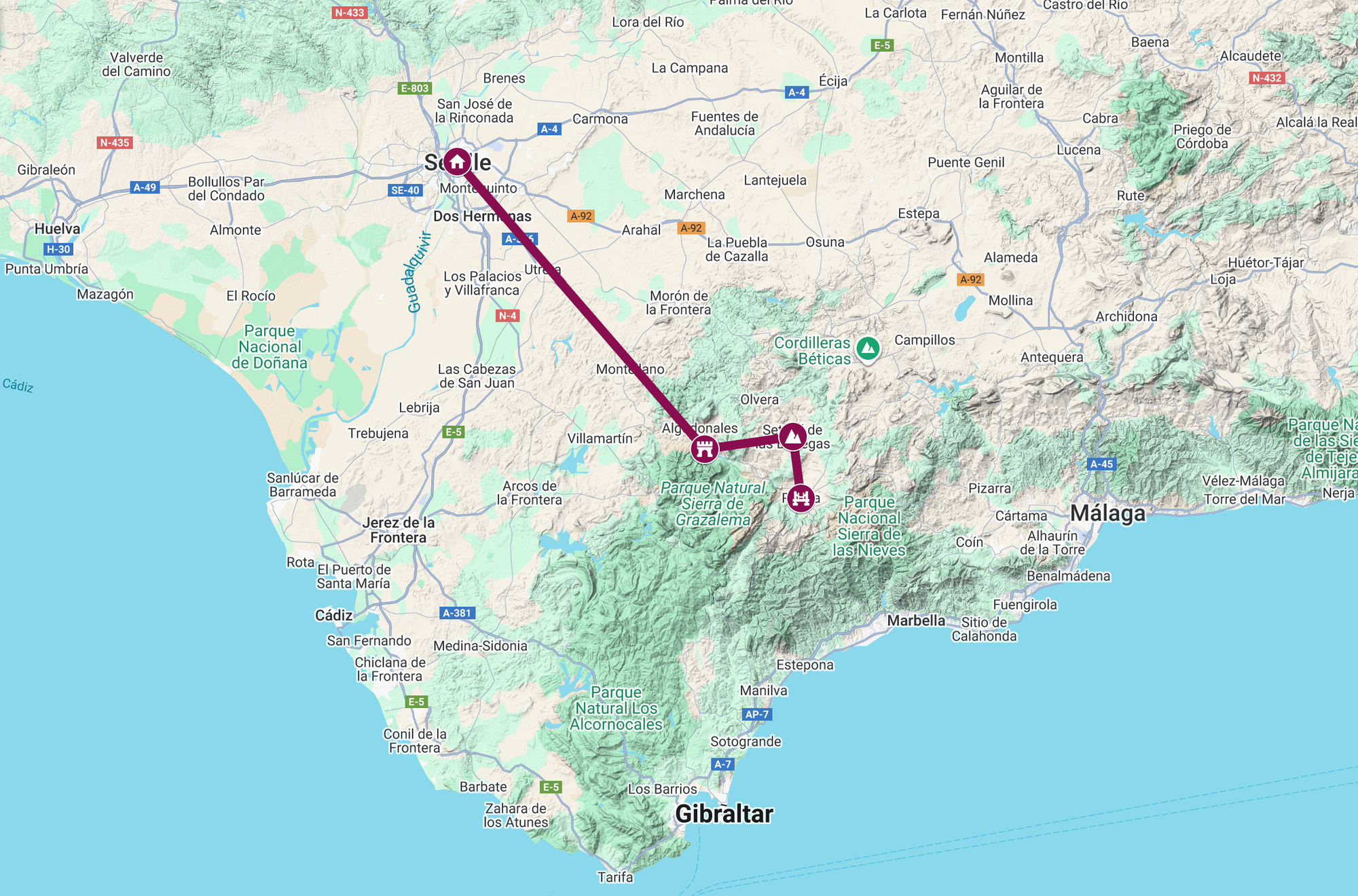

This one-day drive from Seville through the three towns of Zahara de la Sierra, Setenil de las Bodegas, and Ronda is like flipping through the pages of Spain’s history and geography in a single afternoon. If you know nothing about Spain, its climate, its people, or its past, this journey will feel like discovery itself. Every bend in the road reveals something older, stranger, and more enchanting than the last.

Leaving Seville - Into the Sunbelt of Europe

Seville itself is a warm swirl of oranges, gothic towers, flamenco guitar, and evening strolls. But the moment you leave the city, the landscape melts into rolling hills, olive groves, and what feels like a Mediterranean dream.

Welcome to Andalusia, the "sunbelt" of Spain. It's the warmest part of Europe with long summers, gentle winters, and blue skies roughly 300 days a year. Even in late November, daytime temperatures hover around 66°F (19°C), perfect weather for wandering, climbing, and exploring.

As you drive, the land ripples upward, mountains appear in the distance, and whitewashed villages appear along rocky ridges. To an American eye, it looks like the rolling hills of California wine country mixed with the rugged terrain of New Mexico.

And olives. Seas of olives.

Half of the world's olives are grown in this region.

Olive groves stretch endlessly. Andalusia produces more olive oil than Italy and Greece combined. Half the world’s supply grows within an hour of this very road.

These winding routes trace the same ancient pathways used by Roman armies and medieval traders. For centuries, this region stood as the frontier between two civilizations, the Christian kingdoms of northern and the powerful Muslim dynasties that shaped southern Spain.

Stop 1: Zahara de la Sierra - The Castle that Sparked a War

A Storybook Village with Real History

The drive from Seville to Zahara de la Sierra is 59 miles (95 km) takes about 90 minutes. As you round a corner, the village appears dramatically - a ruined Moorish castle perched like a crown on a limestone peak with a turquoise lake spreading below. The whitewashed houses reflect the sun, keeping their interiors cool in summer, a tradition shared by roughly 20 to 30 other pueblos blancos (white villages) in Cádiz and Málaga provinces.

Today, Zahara has around 1,400 residents, but its small size belies its historical significance.

The Strategic Importance of Zahara

The Moors, Muslim peoples from North Africa (mainly present-day Morocco), arrived in 711 AD and ruled for nearly 700 years. Europe was deep in the “Dark Ages,” while the Moorish world thrived in astronomy, mathematics, medicine, and architecture.

They introduced irrigation, algebra, paper, citrus, and the elegant arches and courtyards that still define southern Spain. If the Romans gave Spain its roads and language, the Moors gave it its style. Andalusia became a crossroads of cultures, European, Mediterranean, and North African.

Zahara was one of their frontier watchtowers on the edge of the Emirate of Granada. The castle that stands today took shape mainly in the 13th century. It commands the entire valley allowing defenders to survey dozens of miles of strategic terrain.

This region makes some of the best olive oil on Earth. In Roman times, this wasn't just food; it was currency. Control the olive groves, control the wealth. The battles for this area were about controlling the agricultural economy, not just land.

Zahara’s most dramatic moment came in 1483, when Christian forces of the Crown of Castile from the north captured Zahara in a daring midnight assault. The shock of that raid helped ignite the Granada War, the final stage of the Reconquista that ended Moorish rule in Spain. That same year, preparations were underway for Christopher Columbus’s expedition, which departed from Palos de la Frontera near Seville. Andalusia was shaping both medieval and New-World history simultaneously.

Visiting Zahara

Wander Zahara’s narrow streets and climb to the castle ruins. The village is quite small but public garages make parking in the center of town easy.

For the best panoramic views, take the path up to the ruins of the Moorish Castle and its keep (Torre del Homenaje). This climb offers a spectacular vista over the village and the reservoir.

The walk up to the castle costs €3.50 and is definitely worth the effort. Every step reveals new slices of scenery. Andalusia stretches outward like a painted landscape: olive groves, craggy mountains, and the Zahara-El Gastor Reservoir, completed in 1992, spread below.

Zahara is one of the most photographed white villages, yet you will see more olive trees than people. Its a striking contrast between calm, modern life and centuries of frontier conflict

Stop 2: Setenil de las Bodegas - The Town Inside a Cliff

From Zahara, its a quick 19 mile (30km) drive to our next destination, Setenil de las Bodegas. If Zahara feels like a fairytale, this town feels like a secret.

Architecture That Defies Common Sense

Setenil de las Bodegas is unlike any town you have ever seen. Homes, cafés, and shops are built under massive rock overhangs, the cliff itself functioning as ceiling and wall. The effect is mesmerizing. Some streets are so deeply shaded by stone that you briefly think you’re underground. Others open into bright sunlight.

It’s one of the most unique architectural adaptations in Europe: a town not beside a cliff, not above a cliff, but inside one. People realized the rock itself made perfect “roofs.” They simply built walls under it and moved in. The caves kept food and wine cool, a natural refrigeration system in a land where summer heat can be punishing.

The Story Behind the Name

Setenil comes from Latin Septem Nihil, "Seven Times Nothing." Legend says the Romans tried to conquer the site seven times from the Moors and failed every time. Like Zahara, Setenil became a key Moorish stronghold. These little cliff towns were stubborn, strategic, and worth fighting over. Christian forces finally captured Setenil in 1484, just a year after taking Zahara.

De las Bodegas ("of the wine cellars") reflects the town’s historical wine production, as the caves provided ideal storage conditions.

Historically, locals used these shelters not just for storage but also for raising livestock. Setenil produced eggs, wine, and olive oil, a remarkable adaptation to geography.

Walking Through Setenil

The city has a large public parking garage. It's easier to park in this garage and walk down into the town.

Look for the "Bésame en este rincón" sign. Couples often stop for a photo with this plaque ("Kiss me in this corner") on Calle Herrería.

The village's most famous streets are Calle Cuevas del Sol and Calle Cuevas de la Sombra, where the homes and shops are built directly into the rock formations. Grab a drink at one of the bars carved into the cliffs.

Traditional chorizo, almond pastries such as roscos, pestiños, and tortas are perfect for a leisurely lunch. By 2 p.m., locals are ready to enjoy a siesta, a tradition partly shaped by heat, partly by culture that prioritizes family time and rest.

You can also hike up to the Castillo de Setenil de las Bodegas for a great view of the town. You will pass by the Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación along the way.

Stop 3: Ronda - The City Divided by a Gorge

It takes just 20 minutes to drive the 10 miles (16 km) from Setenil de las Bodegas to our last stop of the day, Ronda, one of the most dramatically located towns in all of Europe.

A Bridge and a Gorge That Take Your Breath Away

Ronda perches atop cliffs split by the El Tajo Gorge, a ravine nearly 400 feet deep. The two halves of the city are connected by the iconic Puente Nuevo (New Bridge), one of Europe’s most dramatic man-made structures. Though it looks medieval, it was built between 1751 and 1793. An earlier attempt collapsed around 1740, killing about 50 people, before engineers completed the bridge we see today.

Standing on the bridge, the gorge drops away beneath you, while mountains and valleys stretch beyond. The chamber above the central arch once served as a prison, with grim rumors of prisoners being thrown from the windows during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939).

Ronda’s Ancient Roots

Ronda is one of the oldest towns in Spain, with a history that stretches back to Neolithic times, evidenced by cave paintings found in the nearby Cueva de la Pileta. The town itself was founded by the Celts in the 6th century BC, who named it Arunda. It was later fortified by the Romans during the Punic Wars and grew in importance, with the nearby Roman town of Acinipo even having the right to mint its own coins.

Following the Roman decline and the Visigoth era, Ronda fell to the Arabs in 713 AD. They renamed the city Izn-Rand Onda ("city of the castle") and made it the capital of the surrounding province. Under Moorish rule, Ronda flourished as an independent kingdom (taifa) for a time, developing a rich culture and sophisticated architecture, including the remarkably well-preserved Arab baths you can still visit today.

Christian forces eventually took the city in 1485 after a brief siege, marking a turning point in the Reconquista. The urban landscape was adapted to Christian roles, but the layers of civilization, Roman bridge foundations, Moorish walls, and Renaissance palaces, remain visible, telling the story of every culture that claimed this dramatic cliffside city.

Modern Bullfighting and Cultural Legends

Ronda is considered the birthplace of modern bullfighting, with the Plaza de Toros (1785), where the Romero family pioneered standing-style bullfighting. This is one of Spain's oldest and most prestigious bullrings. You can take a tour of the ring and its museum.

The city also inspired writers and filmmakers. Ernest Hemingway used the real-life massacre that occurred in Ronda during the Spanish Civil War as inspiration for a famous scene in his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls, which he wrote in Cuba and the US. Hemingway wrote that you should never travel with someone you don’t love—unless you go to Ronda, in which case it’s fine.

Orson Welles spent years in Ronda and loved it so much that his ashes were interred in a well on the rural property of his friend, the legendary bullfighter Antonio Ordóñez, near the town.

Exploring Ronda

Cobblestone alleys, cliff-side palaces, and the gorge’s edge create a cinematic experience. Views from the old quarter let you trace centuries of history in one glance, offering a profound appreciation for a culture that has learned to live spectacularly on the edge.

Returning to Seville: Golden Hour in the Olive Groves

As the sun drops, Andalusia glows. The hills turn honey-gold. Villages shimmer white from far away and the mountains cast long shadows across valleys that have seen centuries of human endeavor. A sense of calm settles over the land. The drive back feels like a long exhale.

You leave Zahara, Setenil, and Ronda behind, but the stories linger, a castle that watched over a turbulent frontier, a town that molded itself beneath a cliff, a gorge spanned by a bridge that defies belief. Each place bears the marks of history, yet life continues with the same quiet rhythm that sustained generations.

These towns reveal what makes this country irresistible: its history, its landscapes, its quirks, its resilience, its flavors, its light. The gentle acknowledgment that life here has been lived for centuries, slowly, patiently, beautifully. The light, the vistas, the villages call you back, reminding you that Spain is a place best experienced slowly, yet also savored in a single, unforgettable day.

Comments ()